Despite this state of New South Wales being the home of the Big Banana, further south in the state capital of Sydney, growing a banana (Musa acuminata) is only barely an option. Some people succeed with careful variety selection, some special efforts to make an unusually warm microclimate and good watering, but a lot of bananas never make it to a sweet yellow. The plants will grow well enough, flower and form fruit, but which is then unlikely to ripen. For months they will hang, green and mostly vainly striving for ripeness through the late winter and spring and just as likely achieve decay first. They may be found in community gardens, perhaps your own garden, or a neighbour’s where they never get used, or in public spaces where bananas may be planted more for the tropical looking foliage than a harvest.

All of this doomed fruit (treated here as a starchy vegetable) can be rescued and used in green banana recipes; in particular curry; and even more particularly one that if eaten before a night out can do a lot to prevent a hangover the next day. I am not talking about a slightly less painful hangover, but a lot less painful. It is a worthwhile, tasty and timely concoction for this time of year. Trust me (but with the disclaimer that this will not prevent alcohol killing cells all over the place, will not prevent you do something stupid or dangerous, and will not help you remember something the next day that you may well then regret having done).

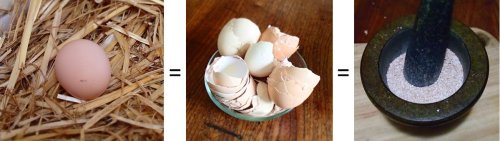

A green banana (Musa acuminata), struggling against decay ahead of ripeness

When harvested and peeled, think of an unripe banana more like a starchy root crop than the sweet fruit that you know

The foundation for this recipe (a curry of green banana, turmeric, coconut and spices) is the most common green banana recipe you will come across, be it Indian or Caribbean – mine just adds a few extra things that, being generally adaptable to the curry theme, come from further hangover-fighting lists, both proven and folkloric. While myth abounds with things to consume once you already have one, hangovers are like STDs – easier to prevent than to get rid of (and generally the result of some poor decisions late in the game).

Common recipes may actually call for plantains (Musa balbisiana and M. balbisiana x acuminata), but a green sweet banana (M. acuminata) is close enough. If you were to use a green sweet banana off a grocer’s shelf green that will ripen happily on a windowsill, cooking time would be brief; but although looking similar, with the stubborn green nuggets I am talking about, I go so far as using the slow-cooker and giving it at least 4 hours – and even then they can come up pretty firm.

Ingredients

Ingredients (and their hangover preventativeness) – serves 4

Green bananas: 5 or 6 of them. These are rich in inulin, a long chain, complex starch that is said to be very good for your guts – gut kindness is very important for hangover resistance, as alcohol is known to mess things up down there. Struggling guts can then increase dehydration, prevent the absorption of stuff you need and make you feel ill. Bananas are also a rich source of potassium which is part of the all-important electrolyte balance, which is a big key to the all-important fight against dehydration (this is the same thing that is behind the reputed value of sports drinks before and after drunken sleep, but does it without being a fluoro factory swill). There is also supposed to be a good amount of B6, the depletion of which is a big part of hangover effects.

Coconut milk: A can or two. A lot of the praise that coconuts get for hangover fighting is written about coconut water (and this may be worth having as a better option than that fluoro sports drink); but for this recipe we are on canned coconut milk and getting some of the same benefits plus the oils which some believe helps by slowing alcohol absorption.

Turmeric: A piece the size of your thumb, finely chopped or grated, plus about a tablespoon of powdered stuff. The curcumin that gives turmeric its vibrant orange hue seems to be the key thing for hangover prevention – possibly the most potent of this entire recipe. I’m not completely sure how it works, but the folk assertion and personal experience are good enough for me at this stage. Seriously, somehow this stuff is hangover magic. Supporting gut health seems to be a big part of it, along with being helpful to liver function, being an anti-inflammatory, helping mop up the acetaldehyde residue of the alcohol and keeping down nausea.

Garlic: Between 2 and 8 cloves minced depending on how much you love it. Garlic is a heavily praised cure-all that contains phosphorus, potassium, calcium, vitamins (including B group) and cysteine. The cysteine seems to be a key helper because it helps in breaking down acetaldehyde produced in the breakdown of alcohol as well as assisting in the production of the amino acid glutathione that is said to be a potent antioxidant and detoxifier (precisely what these last two actually mean in practice I don’t really know, but folk seem to swear by them).

Onion: 1 or 2. Just because you do, even if just for its sweetness when slow cooked.

Kumara: One big one. The kumara is mostly about carbohydrate loading – a very common hangover preventative recommendation, but one that needs to be more than just some greasy chips. As a ‘carbo-load’, kumara probably has the best profile for vitamins and minerals that fit the hangover prevention job – and it suits the recipe best in terms of flavour and theme.

Mushrooms: Just a handful. These have B group vitamins, Selenium, protein and (let’s not forget it’s important) flavour that will get right through the dish..

Ginger: A piece about the size of your thumb or a tablespoon of powdered. Ginger can help as an anti-emetic (easing nausea), acting as an anti-inflammatory in the digestive system and blocking serotonin receptors in the stomach. There are vitamins and the like as well, but perhaps the anti-emetic factor is the most important.

A diverse vegie stock, herbs and spices: You will have to do your quantities by feel, using less if in doubt because it just takes one to come through too strong to wreck a curry. The aim is to get a lot in while still mostly keeping to the principal that this mix (masala) is the flavour foundation of any curry. A diversity of herbs and spices takes something of a scattergun approach hopefully hitting as many of the minor nutrients that alcohol will deplete as possible. On spices I’ve used a stick of cinnamon, pepper, and then small amounts of nutmeg, star anise, fennel seed, cardamom, Sichuan pepper, coriander seed, cumin and fenugreek. For herbs (although largely limited by my garden) I have used lovage, parsley, sage, thyme, bay, rosemary and kaffir lime leaf. The turmeric, garlic and ginger don’t factor here because they are serious ingredients, although they would enter the dish with the herbs and spices.

Miso paste: A lumped up tablespoon. B group vitamins, salt as an electrolyte, and the living culture and enzymes aid digestion, gut health and are said to be rich in antioxidants.

Kimchi: A generous spoonful each or to individual preference (as it gets added separately anyway). KImchi has more (as in lots more) of the three key things top hangover prevention (leaving aside whatever the magic of turmeric is), being: vitamins (especially B group and C), electrolytes (potassium, sodium) and living food. Living, lacto-fermented food is too recurrent a feature in anti-hangover recommendations from too many places across the world not to have some sound basis.

Yoghurt: Enough for each diner to add to suit their taste (or desire to smooth out a rich food). Again, it’s living lacto-fermented food for intestinal health, as well as buffering and carrying some of the flavour strength.

Directions

Sauté cubed green banana flesh dusted with ground turmeric in coconut and olive oils, along with (in rough order) mushrooms, onion, spring onion, garlic, slivered raw turmeric, spices and then douse with coconut milk. Top with more coconut milk or stock as required, allowing for the later addition of kumara. Slow cook for 4 hours, adding some cubed kumara in the last hour and miso paste stirred in well in the last cooling seconds before serving. Serve with a dollop of kimchi and then yoghurt (these want to stay uncooked with their beneficial bacteria alive – if you are serving on rice go with brown (better B vitamins and fibre) and serve the kimchi separate to the curry to lessen the risk of burning the good bacteria to death. To go an extra yard, drink coconut water on the side.

Then drink heavily, with as much of it as possible being water. People will say to make as few drinks as possible bubbly ones, go for pale drinks and not mix grape and grain – but failing that, the intention of the meal is to back you up for a little rule-breaking abandon anyway.

Happy New Year.

Read Full Post »